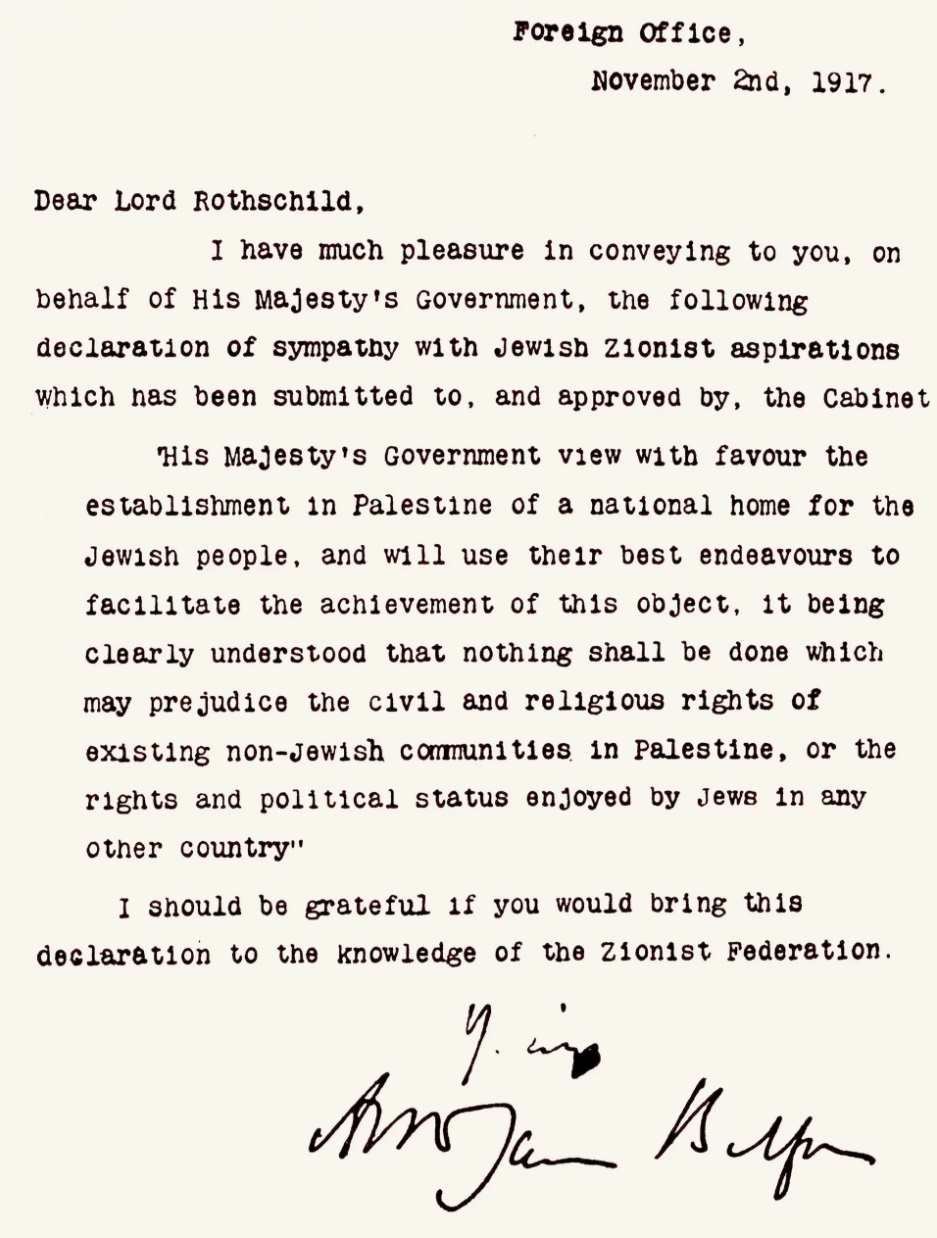

As we mark the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, it is, perhaps, helpful to revisit the neglected history of Egypt’s relationship with Zionism and with Israel. In this essay, I shall be looking at some interesting, yet puzzling historical facts that it would be beneficial for Egyptians, Israelis and others to explore. I shall also be exploring what Zionism meant to Egyptians in 1917 and what it came to mean later.

As we mark the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, it is, perhaps, helpful to revisit the neglected history of Egypt’s relationship with Zionism and with Israel. In this essay, I shall be looking at some interesting, yet puzzling historical facts that it would be beneficial for Egyptians, Israelis and others to explore. I shall also be exploring what Zionism meant to Egyptians in 1917 and what it came to mean later.

Egypt’s reaction to the Balfour Declaration was unreservedly favorable

Contrary to widespread belief, in 1917, and for over a decade after that, the Balfour Declaration was not seen by most Egyptian intellectuals as detrimental to Palestine. Interestingly enough, some Egyptian Muslim and Christian families held parties to celebrate the declaration. Telegrams of gratitude were sent to Lord Balfour by the then-Governor of Alexandria Ahmad Ziour Pasha, a Muslim.

“The Governor of Alexandria Ahmad Ziour Pasha – later Prime Minister of Egypt – went to a party in the city celebrating the Balfour Declaration, that culminated in their sending a telegram to Lord Balfour to thank him,” according to Leila Ahmed in “A Border Passage”.

A delegation of leading Muslims and Christians traveled to congratulate the Jews of Palestine. Many Egyptian Zionist leaders were also Egyptian nationalists and fully committed to the cause of independence from Britain.

Egyptians support of the Balfour Declaration lasted beyond 1917. The Grand Sheikh of Al Azhar officially hosted Chaim Weizmann, co-author of the draft of the declaration submitted to Lord Balfour, when he visited Egypt on his way to Palestine in 1918. The Grand Sheikh was alleged to have made a donation of 100 EGP to the Zionist cause, Egyptian academic and writer Mohamed Aboulghar in his book about the Jews of Egypt confirms the meeting but alleges that actually a donation was made by Weismann to Al Azhar. Weizmann’s cultivation of regional support for the Zionist movement extended to his efforts with the rulers of Hijaz where he executed an accord with Emir Faisal endorsing the Declaration.

The Hebrew University was one of the early dreams of the Zionist movement, in 1918 construction commenced. Ahmed Lutfi el-Sayed, the renowned Egyptian nationalist, political leader and first director of Cairo University joined the celebration for the grand opening of Hebrew University in 1925. In 1944, Taha Hussien, one of Egypt’s most influential literary figures also visited the Hebrew University.

As the Jewish migration to Palestine continued, tensions between the Palestinians and the migrant population increased. The hardline Zionists, referred to as Revisionist Zionists, and early Islamists such as Mufti Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, played a large part in whipping up mutual resentment, fear and anger. These tensions culminated in the 1929 Palestine Riots in late August with the massacres of Jews in Hebron, Safad among others.

The reaction in Egypt remained decidedly pro Zionism well into the first half of the 1930’s, the Government reportedly banned the word ‘Palestine’ from Friday prayers, according to the Leila Ahmed.

The Wafed Government shutdown the sole Palestinian publication with the charge of being pro Palestinian propaganda. Zionist newspapers and magazines continued to operate freely well into the late 1940’s.

Egypt’s Role in Saving Jews from Nazi Europe

The US turned back the SS St. Louis which was full of Jews escaping Germany. Many of those refugees later perished in Nazi concentration camps. Three years later, the US authorities were shamefully still turning back Jews fleeing Nazi Europe. Holocaust Museums mention these stories in detail, yet the fact that Alexandria welcomed Jewish refugees, indeed was only one of a handful of ports, globally, open to Jews escaping from Nazi atrocities that hardly got a mention. For this is another inconvenient history.

Andre Aciman, an Egyptian Jew born and raised in Alexandria, told stories narrated by his family; some Egyptian Jews were not so keen on the influx of Ashkenazi Jews into Alexandria, according to “Out of Egypt”, a memoir by André Aciman.

In readings about World War II and the horrors the Jews faced at the hands of advancing Nazi armies or nationalist partisans, whether Russians, Ukrainians, Serbians or other local populations, it is worth noting that Alexandria, the city that once had the largest Jewish population in Egypt, did not record any attacks on Jewish property and lives when Hitler’s army was just 70 miles to the west.

As the advancing Nazi’s carried out raids on the western parts and the naval port of Alexandria, the number of violent anti-British acts, by Egyptians opposed to the British occupation of Egypt, increased.

Yet no signs of hate or anger against Jews surfaced. The Jews of Alexandria worried about the advancing of the Nazi army but did not fear their Egyptian neighbors, according to Aciman. This is rather strange when so much of the hate propaganda presents Egyptians and Jews as natural enemies. While the self-proclaimed “non-violent” Muslim Brotherhood had indeed started to attack Jews in graffiti, boycotts and worse around 1937 in certain cities, there appear to have been no such attacks during the time of impending entry of Hitler’s army into Alexandria. This should be contrasted with horrible anti-semitic violence Jews witnessed in most European cities.

Joel Beinin offers a concise essay covering Egyptian Jews in the first half of the twentieth century. It is important to note that Beinin has faced relentless attacks from staunch Zionists, much of Beinin’s history can be validated by personal and family narratives such as those of Andre Aciman and others. Aciman too, who wrote a very personal memoir, has also faced attacks from the same quarters that attacked Beinin. Yet both writers’ work calls into question the supposed hate and natural animosity between Egyptians and Jews while never mincing their words on the rise of antisemitism in Egypt.

Yad Vashem, other memorials and Holocaust history in general, offers no special recognition of the role that Egypt and Egyptians played in saving the lives of Jews. A disgusting byproduct of the recent rise of anti-Semitism in Egypt with the wide circulation of books by Holocaust deniers, is that few Egyptians are even aware of this important history that Egypt and all Egyptians should be proud of.

Operation Susannah, more widely known as the Lavon Affair

In the early autumn of 1952, a few months after the July 23 Coup D’etat that led to the overthrow of King Farouk, Mohammad Naguib, Egypt’s first President, joined the celebration of the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashana, at a Synagogue in the heart of Cairo.

Photographs of the event and Naguib’s words were widely reported in the press. Naguib’s message to the Jews of Egypt was that they had nothing to worry about from the 1948 War with Israel and that Egypt’s Jews were just as much an integral part of its fabric as their Muslim and Christian brothers. Naguib had given similar remarks on a visit to the Jewish Hospital in Alexandria among others.

In the immediate aftermath of the 1948 war, a minority of the Jews of Egypt left for Israel and those were mainly Ashkenazi Jews that had come to Egypt as refugees along with a minority of Karaite, Sephardic and other Rabbinic Jews that believed deeply in Zionism. Six full years after the establishment of the state of Israel, Egyptian Jews largely remained in place and minimal immigration had occurred from Egypt to Israel. Naguib’s strategy of fighting Zionism through attempts to integrate Egypt’s Jews further in the society showed good results.

Israeli Military Intelligence, possibly to spur Egyptian Jewish immigration, as well as attempting to derail the Egyptian American relationship, carried out a large number of terrorist attacks in Cairo and Alexandria. The Egyptian born terrorists and their Israeli handler were caught, tried and sentenced. Following Egypt’s defeat in the 1967 war, the imprisoned terrorists were exchanged for Egyptian POW’s. Israel kept their return secret and continued its obfuscation of the Operation. In 1971, Golda Meir, the fourth prime minister of Israel, attended the wedding of one of the terrorists. In 1975, the four terrorists appeared on Israeli TV, where they recounted their story of “heroism”, they have received more honors as recently as in 2005.

Zakryah Mohyeldin, then Egypt’s Minister of Interior, used the very same language as Naguib and talked of Egypt’s Jewish sons as he reacted to Operation Susannah, according to Beinin. Yet hate speech towards Jews was growing in the Egyptian discourse; Muslim Brotherhood followers targeted all Jews regardless of their views towards Israel and intensified their language of hate.

Various attempts to rewrite the history of the Lavon affair continued even into the 21st century. The Israeli MOD continues to redact sections of their disclosures so many years later. Israelis will at some point need to come to terms with the some of the ugly aspects of the history of their nation. Egyptians will need to learn that anti-Semitism plays into the hands of Israel’s right wing which consistently advocates exclusivity as the only way to defend Jews from ever hateful enemies.

Prior to 1967 War, no Egyptian Jews were expelled for being Jewish

Egyptian citizenship laws were first introduced in 1929 after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the birth of Egypt as a modern pluralistic nation-state in 1922-1923. Ottoman nationals and others, who were born in Egypt prior to 1914, regardless of religion, had the choice of becoming Egyptian.

Most Sephardic Jews whose families came to Egypt in the second half of the 19th century sought alternatives to Egyptian Citizenship. It should be noted that Egypt’s native Jews, whether Karaite Jews or Rabbinic (non-Ladino) Jews had roots in Egypt dating back millennia. It is unclear how many Egyptian Jews actually wanted the Egyptian nationality. Beinin talks of increasing difficulties acquiring Egyptian nationality, faced by the Jews, in the 1940’s especially after the first wave of “Egyptianization” laws introduced in 1947. Several Karaite Jews actively lobbied for the “Egyptianization” laws as a way of proving their allegiance to Egypt according to Beinin.

Leftover from the days of outright British and French domination, was a typical colonial justice system that saw local Egyptians subject to Egyptian Law and courts, while the European minorities were subject to their own laws and consular courts. Many of the more affluent Sephardic Jews living in Egypt for two or even three generations did not regard themselves as Egyptians and spoke little or no Egyptian Arabic.

Aciman details the history of typical Ladino speaking Egyptian born Jews who pursued European citizenship. Beinin writes of Jews who actually purchased French and British nationalities without ever setting a foot in these countries. The percentage of non-Karaite Jews who opted for the Egyptian Citizenship is not known but, as Beinin explored, it was limited. Aciman tells a story of a relative who pursued Italian Citizenship following a fire that destroyed Italian birth archives which enabled some Jews who had never set foot in Italy to apply for and obtain Italian citizenship.

According to Benin, “…between the Arab-Israeli wars of 1948 and 1956 a substantial portion of the Jewish elite remained in Egypt and continued to play a significant, though diminishing, role in its economic life.”

The friendly policy towards Zionism by Egypt came to an end in the period leading to and especially following the 1948 War. Once vibrant Egyptian Zionist associations and papers were banned and those openly advocating a Zionist agenda expelled or detained.

Some Egyptian Jews were fervently anti-Zionist and they were typically communists targeted by the wrath of the state and detained with other non-Jewish communists. The first wave of expulsions targeted Zionist and communist Jews who did not hold Egyptian citizenship. This does not appear to have been a large number.

“After 1952 the Italian Egyptians were reduced – from the nearly 60,000 of 1940 – to just a few thousands. Most Italian Egyptians returned to Italy during the 1950s and 1960s,” quoting Italian emigration records.

Those wealthy Egyptians, of various religions, who could manage to escape with even a fraction of their fortunes did so. Needless to say, by end of the nationalization phase, the number of remaining Jews was greatly diminished, but as of then not a single Jew who held Egyptian nationality was forced to leave solely because he or she was Jewish.

Detention of Egyptian Jews, forced surrender of Egyptian Nationality and Expulsion

From the early hours of the 1967 war, the Egyptian authorities started rounding up scores of Jewish men on suspicion of spying for Israel. Several hundred Egyptian Jews were rounded up from all over Egypt and were imprisoned, with members of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, in the notorious Abu Zaabal and Tora Prisons. Marc Khedr tells in detail of his experience from June 6, 1967, until his release over three years later. These Egyptian Jews were subjected to indefinite detention, never faced concrete charges and were never actually sentenced. They were kept in prison just on suspicion of collaboration with Israel, for being Jews.

To get out of Egypt, these Egyptians had to renounce their Egyptian Citizenship, undertake never to return to Egypt and were taken from their prison cells straight to the airport to board flights to France. Khadr’s use of language, referring to concentration camps, invites two unfortunate comparisons.

The first comparison is to the Nazi concentration camps, the other to the other political prisoners who were there before the capture of the Jews and whose detention outlasted theirs. This in no way diminishes the injustice and suffering that Mr. Khedr and other Egyptian Jews faced. Mr. Khedr, a Karaite Jew whose mother tongue was Egyptian Arabic and whose original name Mourad Amin Khedr, a typical Egyptian name, was fully Egyptian in all aspects of the word. It was bigotry and discrimination, suspicion and mistrust by the State and fellow Egyptians that led to the loss of homeland for Egyptian Jews and the loss for Egypt of its own Jewish people.

Where are we 100 Years after the Balfour Declaration?

As mentioned above, history has been rewritten by both Egypt and Israel to suit the chosen narrative. The fact that Egyptian Jews were often in the forefront of Egypt’s liberation movement has been conveniently forgotten or ignored. The Egyptian’s support for the Balfour Declaration has been forgotten and history was rewritten to erase it. The role Islamic Nationalism has played in support of the ascendence of the uncompromising radical Revisionist Zionism can be seen clearly from the early 1920’s. Later, Revisionist Zionism came to dominate the Zionist discourse. The role Zionism played in strengthening Islamism, Islamic and Arab Nationalism as a counterbalance to it continues to our present day.

The lack of recognition of Egypt’s role in saving Jewish lives in the dark days of WWII should be an embarrassment to Egypt, Israel and world Jewry. It doesn’t fit the narrative of animosity. The narrative of Egypt throwing out Jews and the exodus of Jews from Egypt fits with the, now dominant Zionist narrative. Egypt lost a great deal from the exodus of the foreign communities whether Greek, Italian, Turkish, French or British. It is crucial to see the exodus of Egypt’s Jews for what it was and it was primarily an exodus of foreigners. The bigotry, racism and discrimination that followed several wars with Israel is abhorrent and should not be defended. However, it does not tell of ancient animosity between Egyptians and Jews, indeed it highlights the opposite. Some in Israel are beginning to question the language that has been used to describe the Jewish exodus from Egypt.

It is hard to reach a conclusion as to what the Zionist movement’s true aims were: did it really intend to protect the interests of the native Palestinian population or was Revisionist Zionism and Zionism the same all along with only some differences in outward appearance? As late as 1935, the main strand of Zionism continued to reject the idea of a Jewish state, this was the Weismann Zionism, whereas Revisionist Zionists led by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a Russian Jewish Revisionist Zionist leader, clamored for the abandoned colonialist vision of Theodor Herzl. Was all of this just a Zionist facade?

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, did Revisionist Zionism provoke the emerging Islamic Nationalism and the Islamist movement or did the later unintentionally aid Revisionist Zionism and help it dominate the whole Zionist agenda? Were the Egyptian political elite subject to a conspiracy so that they fell for the “treachery” of the Zionists or were they supportive of a benign form of Zionism and were late in recognizing the emergence of the violent, racist, supremacist Zionism that triumphed late in the 1930’s? Answers to these questions determine how Egypt’s early support for Zionism can be viewed.

Let’s learn from the mistakes of the last 100 years. Let’s confront this inconvenient history and use it as a basis for the possibility of coexistence. Millions of Palestinians continue to live in refugee camps, millions of Palestinians continue to languish stranded under cruel occupation. The image of the Palestinians living literally underneath high speed “Israeli only” trains linking Jerusalem to neighboring “Jewish only” communities will forever stay etched the memory of many of the people who have seen it, it should be a source of shame for Israelis and Israel’s supporters.

It is time to actively work towards achieving the second half of the Balfour Declaration. Historical examples of peaceful and positive coexistence are not limited to Egypt. It is time to remember that the majority of the Jews of Hebron and Safad were actually saved from the massacres, not just by the British Army, but also by their Palestinian neighbors. It is time to uncover more inconvenient history and use it as the basis for a better future. Personal narratives of Palestinians, like those of Fay Afaf Kanafani, tell of similar stories of successful coexistence between Palestinians and Jews even into the 1940’s. Digging into the truth of what really happened on the ground may prove harder than that of Egypt because of the relatively advanced nature of the Egyptian press and political structure compared to that of British Mandate Palestine. The Egyptian experience should nonetheless help in looking at what is possible over the next 100 years.

Ayman S. Ashour

This essay was first published by Egyptian Streets here.